Claude Code writes Optional[str]. You want str | None. It catches exceptions with bare except Exception:. You require specific exception types. It uses List[str] from typing. You’ve standardized on built-in generics.

Claude Code is trained on millions of codebases with millions of conventions. Your codebase has one set of conventions: yours. And Claude Code doesn’t know them unless you tell it.

The obvious solution is CLAUDE.md. Document your standards there, and Claude Code follows them. This works until your standards hit a few dozen lines. Beyond that, problems emerge. At 400 lines of Python conventions, architecture rules, and testing patterns, Claude Code starts missing details buried in the middle. Critical rules get overlooked.

Alignment Challenges at Scale

It only gets worse in large codebases and monorepos: multiple apps, packages, infrastructure, services, each with their own conventions. Your backend has Python standards. Your frontend has TypeScript conventions. Your data pipeline has its own architecture rules. You could organize these into folders with dedicated CLAUDE.md files, but domains don’t always map cleanly to directories. A service might touch three domains. A shared library might have different rules than the applications consuming it. Standards sprawl across files, and Claude Code loads context it doesn’t need while missing context it does.

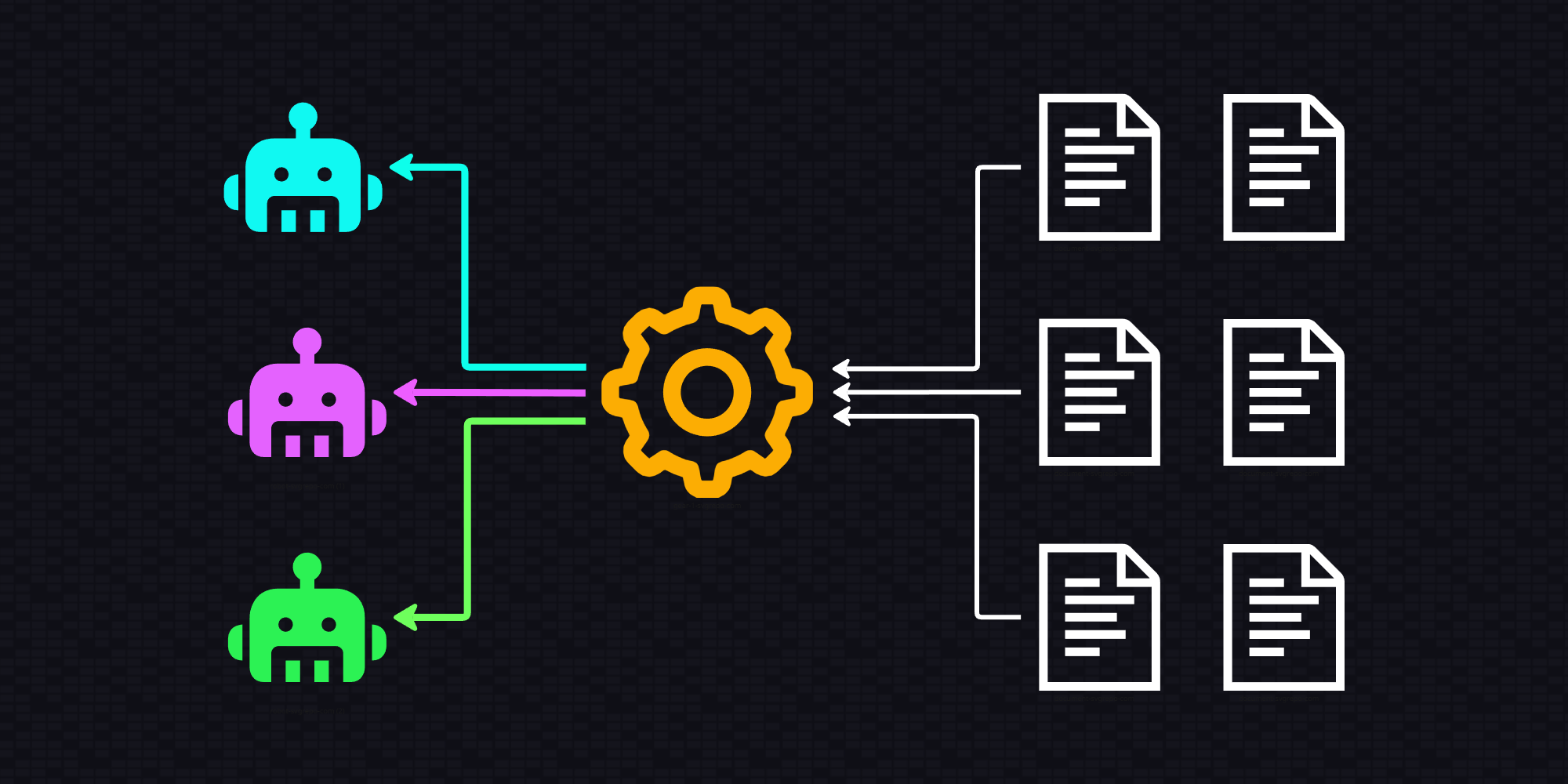

The problem compounds when you start using subagents. These are specialized Claude Code instances you spawn for specific tasks. A common scenario is to use an engineer agent for implementation, a code reviewer for validation, and maybe a dedicated architect for design decisions. Each subagent runs in its own context, which is precisely why they’re useful: they stay focused on their task with dedicated context and without the baggage of the entire conversation.

But that isolation creates coordination challenges. In a multi-domain codebase, you might have a core-engineer and core-reviewer for your shared libraries, a backend-engineer and backend-reviewer for your services, an infra-engineer for your deployment code. Each domain has its own conventions. Each engineer-reviewer pair needs to enforce the same standards so the engineer produces code that passes the reviewer’s checks, and both need the right standards for their domain.

Keeping these agents in sync manually is a maintenance nightmare. Update a Python convention and you’re touching six agent files. Miss one, and your backend-reviewer enforces rules your backend-engineer doesn’t know about.

The fix isn’t better documentation. It’s compartmentalized rules that agents fetch on demand. Each agent gets exactly the standards it needs for its task, nothing more. Need-to-know context, guaranteed consistency.

Provide the Right Context When It’s Needed

What if we could provide all the relevant context dynamically for each agent? Not stuffed into CLAUDE.md, not duplicated across files, but injected at the moment the agent starts, based on what that specific agent needs.

Claude Code makes this possible through hooks. Hooks are scripts that run automatically at specific points in Claude Code’s lifecycle: before a tool executes, after a file changes, or when a subagent spawns. They let you intercept and augment Claude Code’s behavior without modifying your prompts.

Here’s how it works: when a subagent spawns, a hook scans the agent definition file for references to your standards. It finds those references, resolves them, and injects the relevant sections directly into the subagent’s prompt. The agent receives its task instructions along with the exact policies it needs to follow. Think of it like handing an employee their assignment along with the relevant sections of the company handbook.

This works well because the context is strongly associated with the task. We don’t have to rely on the agent discovering weakly associated system prompt or memory content.

Unambiguous Reference Notation

Here’s what that looks like in practice. I came up with a notation system that unambiguously references sections in my standards documents. An agent definition includes a Required Policies section:

## Required Policies

["§PY", "§CORE"]

Before the agent starts, a hook invokes a policy server that scans the agent file for these special references. It resolves them against a set of well-maintained policy files, pulls the specific content, and appends it to the prompt starting the agent.

To align subagents, just have them reference the same policies. My engineer and code reviewer both include ["§PY", "§CORE"]. When the hook resolves these references, both agents receive identical policy content. No duplication, no drift, no conflicting interpretations.

The policy server handles the mechanical work: fetch the sections, resolve any cross-references, return exactly what’s needed. Request §PY.2 (Runtime Safety), get that section plus any sections it references.

A Concrete Example

Policy files live in .claude/policies/. They’re regular markdown with sections marked using § notation. The system scans all files in the folder, so you can organize standards however you like and files can reference each other. Here’s a simplified example:

## {§PY.1} Python 3.14 Type Standards

All Python code MUST use Python 3.14 type syntax.

### {§PY.1.1} Built-in Generic Types

Use built-in generic types. NEVER import `List`, `Dict` from `typing`.

### {§PY.1.2} Union Types with Pipe Operator

Use `|` operator for union types. NEVER import `Optional` or `Union`.

## {§PY.2} Runtime Safety

### {§PY.2.1} Specific Exception Handling

Catch specific exceptions. NEVER use bare `except Exception:`.

See §PY.1 for type syntax in exception handlers.

For guidance on writing effective policies (structure, examples, what good and bad look like), see the §META policy standards, which is itself a good example of how policy files should be structured.

With the policy file in place, subagents can now reference sections by notation. You can cherry-pick what you need, or pull in entire sections or documents.

§PYfetches all Python policies (every§PY.*section)§PY.1fetches the entire Type Standards section with all subsections§PY.2.1fetches just the Specific Exception Handling subsection

Cross-references resolve automatically. When §PY.2.1 mentions §PY.1, both get included.

Setup

Setup is straightforward. Install the policies plugin:

/plugin marketplace add rcrsr/claude-plugins

/plugin install policies@rcrsr

Store your policy files in .claude/policies/ using § notation. Add a “Required Policies” section to your agent files with the references you need. Policies auto-inject when the agent runs.

The plugin also includes commands for generating policies from existing code patterns (/policies:create-policies) and auditing them against quality standards (/policies:review-policies).

For advanced configuration or alternative integration scenarios, see the mcp-policy-server project.

Why This Beats Semantic Search

This isn’t RAG. There’s no “find relevant content” step, no vector embeddings, no semantic matching.

Request §PY.1.1, get §PY.1.1. Exact lookup. Same input always produces the same output.

Your subagents fetch §PY.2.1 and get identical content about exception handling. Not “similar content about exceptions,” but the exact same text. That’s what creates alignment.

Summary

Subagent alignment isn’t a prompt engineering problem. It’s a shared context problem.

When subagents share the same policy sections, they enforce the same standards. When cross-references resolve automatically, nothing gets missed.

Same policies. Same standards. Predictable behavior.

Explore more:

This article was originally published October 2025 and revised January 2026 to reflect the evolution from MCP server integration to the hooks-based policies plugin, with updated examples focused on software engineering workflows.